The annual True/False film festival has rolled into my fair city once again. Once again, I'll be offering notes from the interior.

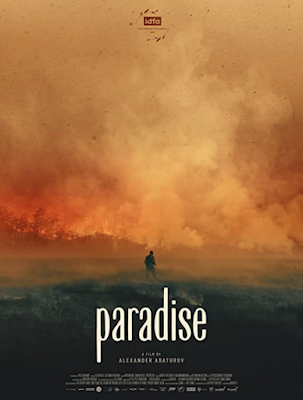

The impending climate apocalypse has been on the mind of documentary filmmakers for years at this point. They point their cameras at any number of canaries in the coal mine, be it arctic ice, desertification, climate-induced wars, and what have you and they still have no effect in changing the direction of the world. It sucks to be a Cassandra. Always has. The subject of Paradise (2022, directed by Alexander Abaturov) is wildfires in Siberia, but that's only cover for its real concerns. It points an accusing finger at the true authors of climate change while suggesting that community and mutual aid is the way we might survive it. Maybe.

Paradise doesn't start with the fires though. It starts with a car doing donuts in the snow to jazz music. Then it moves to a man tending a fire in the winter night. The man at the fire has a story to tell. Then the film focuses on a little girl learning her lines for a school pageant. In the pageant, she plays a personification of the wind speaking to a mountain. She lives in Shologon, Siberia, in the taiga that lately has burned every summer. The village has been spared thus far, but in the latest fire season Shologon is in the path of what the villagers call "the dragon." Everyone in the village is fighting the fires, driving deep into smokey landscapes to set backfires and firebreaks at the direction of the smoke-jumper from Moscow. Unfortunately for the village, Russian law prohibits the government from spending money fighting wildfires if the cost of the fight exceeds the value of of the land. Two thirds of the way through the film, the smoke-jumper is recalled and the vilagers find themselves on their own.

At one point mid-film, one of the village kids in Shologon compares their situation to the zombie apocalypse--American horror movie tropes having apparently ringed the planet. It's an apt comparison, though, because it's a portrait of a society collapsing as their institutions fail. One of my favorite elements of zombie movies is that disquieting moment when the audience and the characters realize that the machinery of civilization has stopped, when the characters are isolated against the tide of whatever apocalypse awaits them. In this film, that moment is when the man from Moscow is recalled. At that point, the planks of civilization are no longer propping up Shologon and the villagers are faced with the choice of fleeing before the flames, or continuing to fight them. There's a shock of betrayal in the last parts of the film, but no time to feel the sting for long because the job of survival is waiting. In this regard, the film contains a kernel of uplift, which it leans into in its epilogue, set in the winter long after fire season has passed. Eventually, we get a reprise of the car doing donuts in the snow.

But Paradise knows this is a false sense of uplift. It knows that the fire season is coming again. It knows that the institutions are unreliable. This movie is set before Russia's invasion of Ukraine, but at this point, the filmmakers and the audience both know that the men who we have watched valiantly fight the fires will shortly be facing another apocalypse. Moreover, the broader global implications are reserved for a title card at the end, which tells us that Siberian wildfires have spread ashes across the North Pole, which has never happened before in human history. The calamity dwarfs one Siberian village in the middle of nowhere.

Paradise knows, too, where to point the finger. It skips over the local politics and singles out the real authors of the calamity in the first place. Russia is a petro-state and by pointing an accusing finger at the Russian state for its institutional neglect, it's pointing fingers at the fossil fuel oligarchs who will give up their hold on power and the economy at the cost of the planet itself. It's careful to avoid making this explicit, but the implicit drenches the negative spaces of the film. It hides its contempt for the powers that be by focusing for a while on the mundane job of fighting the wildfires and by spending time with the villages. The mere act of wandering among the flames out in the taiga is a kind of crucible, but the film isn't strictly concerned with its agon. There's a gallows humor, too. The scene with the women of Shologon driving out to the fires in the back of a truck is filled with gossipy humor that stands out among the smoke and terror and renders these people as real people with real concerns rather than as props in a film with grand activist ambitions. But it goes beyond this, too. The landscape in which most of this is set is an alien world of smoke and snakes of fire. The men wandering among the burning trees and bushes seem like they've been banished to some terrifying underworld, in which the sun is occluded by the smoke and where every breath is a chore. Stray from the path, this film suggests, and you will burn. Indeed, Paradise frames the entire thing as a mythic struggle against ancient elemental forces. There's a startling insert cut of a girl in a white dress--the girl who is introduced rehearsing the role of the wind in the school pageant--standing in the fields outside the town as the calamity engulfs everything. This kind of shot isn't the sort of thing you usually see in a strictly observational documentary, and this film, for all its careful non-fiction rigor is not a conventional documentary. The girl becomes a personification of the wind and the fire becomes a dragon. This is an epic of sorts, with primal, operatic images and deep mythological roots.

Paradise is the documentary as movie, rather than as agit prop or as journalism (though both impulses are certainly there in the negative spaces), and as such it insinuates its ideas into an audience's consciousness as a smuggler. Its basic elements are the province of entertainment: visual spectacle, archetypal characters, even a happy ending of sorts, though that's ambigous to say the least. And it's not an ideal film in this regard. It sets out to structure its story in seasons, including a title card to denote one season, then it abandons the idea completely without a backward glance. This is a minor flaw, though. It's an idea that doesn't pan out rather than a crippling mistake that undermines the whole film. At its best, however, it's a terrifying harbinger, one that amplifies the doom that's keening on the wind. The conflagration is here, it says. The world is already burning and our institutions will not save us.

This blog is supported on Patreon by wonderful subscribers. If you like what I do, please consider pledging your own support. It means the world to me.

No comments:

Post a Comment