Of the films Cary Grant made with Alfred Hitchcock, To Catch A Thief (1955) is the one that has been dismissed most often by the director's admirers and detractors as a lightweight "entertainment." A bauble, if you will. Candy. Empty calories. It is certainly a film conceived of and drenched in the glamour of classic Hollywood. It pairs the biggest star in the world opposite one of the most unattainable beauties of its era. It sets its action against a backdrop of wealth and intrigue on the French Riviera and Monaco. It hobnobs with the idle rich. It's a caper film about an international jewel thief. It's pop filmmaking at its most trivial. It's a fantasy. And sure: It lacks the sinister undertones of Suspicion, the complex psychological depth of Notorious, and the stakes and forward motion of North by Northwest. But to look only at its surface gloss is a mistake. Smuggled under the candy coating is a story about hollow men in a Europe still recovering from the calamity of the great wars, in which bad men never escape their pasts and visit their sins on the next generations. It's a significantly darker film than its reputation would have you believe. It's also a portrait of Hollywood films in transition from the studio era--whose days on the stage were numbered--into a conversation with the rest of the world. This was partially filmed in Europe, perhaps with a propagandist intent. Like many American films of its era, it's a weapon in the Cold War, when Hollywood movies that wallowed in a gaudy affluence were a bulwark against the gray economic heat death of Soviet communism. All weapons should be so brazenly sexual.

The story follows John Robie, "The Cat," a former jewel thief whose crimes were pardoned because of his service to the French Resistance during the war. Ten years after the war ended, someone who knows his methods has taken to stealing jewels from the rich clientele who come to play on the Riviera. This puts Robie in a bit of a bind. He's still on parole and the police really like him for the crimes. Evading the Sûreté as they come to arrest him in his home, Robie makes his way to the beach resorts in Monaco and Cannes, intent on bracing his former associates for information. They are none too happy to see him. They believe him to be guilty, too, and thus a menace to their own lives and freedom. He proposes to catch the thief at their own game, using his own skills to run them down. To this end, he consults with H. H. Hughson (John Williams), the insurance man representing the victims and obtains a list of likely targets. One such is Francis Stevens and her mother, Jessie (Grace Kelly and Jessie Royce Landis, respectively). Francis in particular has her eye on Robie and flirts with him mercilessly. She's on to him, sure. But apparently she likes dangerous men. The Stevenses have a fortune in jewels, an ideal target for the Cat. Robie hopes to use them as a stalking horse. Francis has other ideas, but those other ideas fly out the window when her mother's jewels are robbed. She blames Robie, providing him with yet another incentive to clear his name. Circumstances finger another man, though: Robie's ex-accomplice, Foussard, who attacks Robie in the night and is killed in the scrum. Foussard's daughter, Danielle, blames Robie for her father's death. The police still suspect Robie. Robie knows that Foussard couldn't have been the thief. He had a wooden leg after the war so climbing over rooftops was beyond his ability. He decides a fancy costume ball is the ideal venue to flush the Cat into the open...

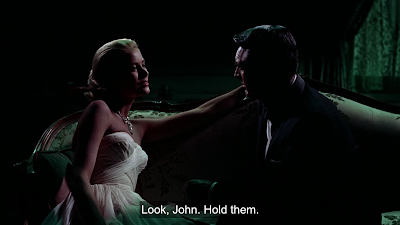

Tone and idiom are everything. Were it not for the light comedy and technicolor, To Catch a Thief might be mistaken for film noir. John Robie is an ideal hero for such a framing: a man with a shady past whose life is upended when that past visits him in the present. There's a femme fatale and a cadre of former associates with malice in their hearts. The elements are certainly there, and with a slight twist of its ending, it could be a dark film indeed. But it's not dark and it's not noir. No one could make that mistake. If there's a slight hint of noir it's like salt on caramel. It's an undertone rather than the main flavor. A better frame of reference might be films from before the war like Trouble in Paradise or Jewel Robbery, in which a gentleman thief makes off with both the loot and the leading lady's heart. It certainly has the same kind of flair for the double entendre one finds in Lubitsch. This film has a doozy of an entendre, double or otherwise. When Grace Kelly is taunting Cary Grant with the jewels hanging above her plunging decolletage; she's not talking about jewelry here at all:

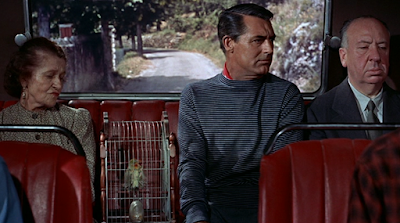

While this is technically one of Hitchcock's "Innocent man wrongly accused" films, Robie is anything but innocent. While he runs from the cops at first, he seems more in command of events than Hichcock's usual patsys and he carries a larger than usual burden of guilt. He's a career thief, after all, and he knows where the bodies are buried. When John Robie runs, he knows where he's going and where he'll find his answers. Grant's performance as Robie is unflappable. He's a man of experience and Grant wears that experience like an expensive suit of clothes, even when he's done up as a parody of a rural Gallic retiree in white pants and striped shirt. Grant wears the hell out of clothes in this film, too, as does his leading lady. This film is costume designer Edith Head at her most ostentatious, which is saying something.

To Catch a Thief doesn't have one particular bravura sequence to make auteurist film viewers salivate. There's no equivalent to the crop duster scene in North by Northwest or the merry go round climax of Strangers on a Train, so it's not as obvious to a casual viewer that To Catch a Thief is the work of a master at the top of his game. Hitchcock strives for invisibility here, as much as he ever did during his peak years (which isn't very invisible at all). Rather, this is a film where its average scenes are so precise that in the aggregate the film becomes a finely machined engine. The devil is in the details. Take the scene where Cary Grant arrives on the beach at Cannes after jumping from the boat piloted by Danielle. This is an example of how a good director moves his chess pieces around the board. Grant is the object of the frame, and Hitchock makes sure you're watching him, but he's placed another actor into the frame as Grant makes his way ashore, a woman in a gold and white swimsuit. This woman notices Grant from behind sunglasses. Grant lays down on the sand; the camera is still following him and the director cuts to a closer shot as he comes to rest, only to have a shadow loom over him. Then follows a shot from Grant's point of view looking up at a looming figure backlit by the sun. The looming man says "Monsieur Robie?" Then back to Grant in the master shot, who nods, gets up, and follows the looming figure off camera. The camera does not follow him, though. Instead, we are left with the woman in the gold swimsuit in the master shot, then Hitchcock cuts to a closer shot of her. It's not immediately obvious that this woman is Grace Kelly, because Hitchcock and Edith Head have disguised her a bit with a turban to hide her blonde hair and sunglasses to hide her features. She doesn't say anything in this sequence of shots. But leaving the camera on her as Grant leaves the frame notes her significance. There's no significant dialogue in this sequence except for Robie's name, so what you have is pure cinema even if it's not showy at all. Hitchock guides the audience's eyes around the frame with exact visual cues. Moreover, it seeds the fact that she's on to Robie from the get go and becomes his accomplice from the very start of their acquaintance. It's an efficient expository scene that codes its information in images rather than text. The movie as a whole is like that, down to Grace Kelly wearing a ridiculous gold lame gown at the ball during the climax whose color recalls the swimsuit in which the audience first sees her.

The picnic scene is a case study in character coding, too. The first part is the drive. There are a lot of car scenes in Hitchcock films, maybe because they're a way to let characters talk while they're doing something. Almost all of Hitchcock's car scenes are filmed with rear-projection, and rely on the actors to carry them. In this one, Frances Stevens drives fast, perhaps recklessly, in a way that unnerves John Robie. This is the first indication that she's attracted to danger. As they have their picnic, she tells him outright that she knows he's John Robie the Cat, even as he continues to deny it. At the villa, she picks up on the fact that he's casing the place, and wants to know what the plan is. She acts as if she wants in on the job. She's not a "nice" girl, or, more accurately, she likes to role-play as a girl who isn't "nice."

A further example of Hitchcock exerting his influence on elements that another director might ignore can be seen in the way he stylizes the rooftop environs of his cat burglars. The first couple of heists depicted don't even bother with the details of the robberies: they consist of shots of a black cat walking across roofs that are lit with an unearthly green light. It elides the robberies but gives nothing of the details. It's enough to know that they've happened. The rooftop set isn't naturalistic at all. The unnatural color with which it's lit aestheticizes it and removes it a bit from reality while the various angles of the roof and the chimneys break the film's horizon line into an expressionist collection shapes that only approximate a roof. Again, this is pure cinema and completely unnecessary, until the end of the film when it becomes a dangerous playground where Robie plays cat and mouse with the impostor and with the bullets pinning him down from below. This all has an effect. It's all a cumulative sum of details that distinguish a film that is more than just "well directed" (as if "well directed" was even something that is common among films), and never mind the additional auteurist baggage of personal themes and consistency of technique and image. That's there, too. One thing a viewer might notice if she's seen a bunch of Hitchcock films is the way he re-stages the end of Saboteur, in which the ending of the film depends on the hero saving the life of the villain in order to clear his name. In both films, the villain dangles from the hero's hand over a fatal height. This film revises the end of Saboteur a little, changing the outcome. Hitch would revisit this formulation again in North by Northwest, when he completely reverses the positions of the hero and the villain, changing the outcome yet again.

It should be noted that one of the flaws of auteurism is the fact that all of the tools that directors use to lead the viewer through the narrative are in collaboration with the other filmmaking departments. The beach scene I've referenced doesn't have the shadows of a film like Suspicion to lead the eye, so Hitchcock uses costume design, movement (Grant is the only thing moving in the first two shots of that sequence), and the presence of movie stars in the frame. Movie stars, it should be noted, are often stars because light just bounces off of them differently. Other scenes rely on production design and lighting. None of the director's primary job of blocking the frame and the movement of the actors and cameras exist in a vacuum. Maybe that's why Hitchcock prefered the pre-production process to actual filming. He could keep his own vision without anyone else's input.

This is the only film Grant made with Hitchcock that really leans into the Grant persona as a movie star, though I suppose no film starring Cary Grant can avoid this element entirely. Both Suspicion and Notorious explore the more sinister possibilities of Grant's polished veneer, while North by Northwest almost seems gleeful in the way it punctures Grant's stardom. By contrast, To Catch a Thief luxuriates in it. The world Grant moves through here is a dangerous one of thieves and murderers, true, but it's also one of glamour and fantasy. He moves through it with a self-assured calm. He never really seems frantic in this film, or disheveled. Characters in the film itself take note of this, particularly this look that Jessie Royce Landis, playing the elder Mrs. Stevens, directs Grant's way:

Hitchcock's staging treats Grace Kelly the same as Grant. The camera is enamoured of her. Kelly was Hitchcock's favorite leading lady and more than in his previous films with her, he lets the camera surrender to her beauty. He eventually dresses her like a fairy princess at the end of the film (the dress resembles the one Belle wears in Beauty and the Beast forty years later, so it sticks in the cultural massmind). The film prefigures Kelly's marriage to Prince Rainier of Monaco. Over and above the plot of the film and the director's suspense techniques, this is a film about watching very beautiful people court each other, and Hitchcock does not interfere with that impulse at all. Indeed, he acts as a facilitator.

|

| Bond. James Bond. |

To Catch a Thief found Grant at a crossroads. After the failure of his previous film, Dream Wife, Grant thought his career was over. Between 1953 and 1957, To Catch A Thief was the only film in which he appeared. The period was the most idle of his career. He was considering retirement at age 49. To an extent, To Catch a Thief gave the actor a second wind. In 1957, he would appear in three films and then two more in 1958. Some of Grant's best-remembered films lay ahead. None of that would have been possible if To Catch a Thief had failed. It DID fail with critics, who have largely dismissed it to this very day, but not with audiences. It was a gigantic money-maker. It is significant that when Alfred Hitchcock was himself coming off the financial failure of Vertigo three years later, he turned back to Grant to resurrect his status as a hitmaker. It's said that Ian Fleming wanted Cary Grant and Alfred Hitchcock to bring James Bond to life after seeing North by Northwest, but To Catch a Thief strikes me as more a Bond-like film. The image of Cary Grant in the casino lacks only the line "Bond, James Bond." So while To Catch a Thief may be a slight "entertainment"--and for what it's worth, I think it's more than that--it seems to me that it is undervalued for its influence on the careers of its principal creators and on cinema more broadly. It's also a pretty good film.

My other posts on Cary Grant. Only about sixty more films to go:

This is the Night (1932)

Enter: Madame (1935)

The Eagle and the Hawk (1933)

The Last Outpost (1935)

Wings in the Dark (1935)

Only Angels Have Wings (1939)

Penny Serenade (1941)

Suspicion (1941)

North by Northwest (1959)

This blog is supported on Patreon by wonderful subscribers. If you like what I do, please consider pledging your own support. It means the world to me.

No comments:

Post a Comment