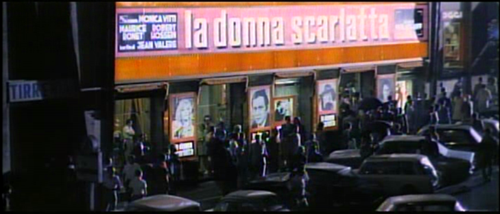

I just about blew my drink through my nose when I saw that shot. I didn't remember it, but I know the movie pretty well, so it means everything.

The opening suspense sequence in between the glass doors is still a corker.

Anyway...

Reprinted from my web site (and my old blog).

314. and 315. So I saw Marty Scorsese's The Departed (2006) again a couple of weeks ago. It's an okay film, but something about it has been gnawing on me since it was released.

A little background: The Departed is a remake of the Hong Kong cop thriller, Infernal Affairs (2002, directed by Wai-keung Lau and Siu Fai Mak). Both films follow the intersecting paths of two undercover agents. One agent is a cop placed in the confidence of a mob boss. One agent is a mobster planted in the police by that same mob boss. Neither man knows the other, though both are aware of the other's existence. A cat and mouse game follows. Both films have the equivalent of an all-star cast. I prefer the cast of the original, stocked as it is with some of my favorite actors anywhere in the world (Tony Leung and Anthony Wong in particular). I'm less sanguine about the cast of the remake. I've never warmed to Jack Nicholson or Matt Damon, and Leo Di Caprio is laboring in the shadow of Tony Leung's astonishing performance in the original item. But that's neither here nor there. If you haven't seen the original, you'll love the remake. If you have seen it, you'll probably like the remake. Maybe.

If you have an interest in seeing either film, but haven't yet, stop reading now.

Still with me? Okay.

Infernal Affairs is a terrific film. The Departed isn't as good, but it's not bad. It follows the original's story pretty faithfully until the end. The end. That's where I get hung up. At the end of Infernal Affairs, the Andy Lau character betrays his mob boss and goes over to the cops. To do this, it's necessary to wipe his opposite number off the ledger and turn his back on his murder. He gets away with everything (well, not quite, but enough). Andy Lau's saturnine face is inscrutable through all of this, and there is a remarkable ambiguity built into this ending. That's the ending that most of the world saw. There is an alternate ending made for the mainland Chinese market. The censorship standards in the mainland market require that corrupt government officials be brought to justice in their movies--a convenient fantasy, one must admit, given the rampant corruption known to exist in China's ruling Communist party. In that version, Lau's character is arrested at the end of the film and hauled off to jail. This is in opposition to the spiritual thematic concerns of the movie, but try telling that to a censor. Irony is just one of many virtues lost on censors.

Apparently, Americans are subject to the same rigid censorship requirments. The Departed changes the ending even more thoroughly than the ending intended for the mainland Chinese. The remake sets up a situation where someone else in the police department knows the identity of Leo Di Caprio's character, and once Leo's character is dead and Matt Damon's character is seemingly scott free, he shows up and puts a bullet in the brain of Damon's character. Evil, then, has been punished. To underline this ending, the camera pans up to the balcony where a rat scuttles across the railing, as if to say: "Get it?" This would be disappointing in any film, but for it to occur in a Scorsese movie is a travesty. There is the suggestion in this turn of plot that not only do the big multinational companies that keep Americans--and by proxy most of the rest of the world--sucking like infants at the teat of bourgeois media hold their audience in even lower regard than the Communist Chinese. And they do it in even more brutal fashion. Let me give you two other examples:

A decade ago, someone got the bright idea of remaking Alfred Hitchcock's Dial M For Murder. This film, retitled A Perfect Murder, actually manages to improve on the original item in several important ways and largely sidesteps the shadow of Hitchcock until the ending. In the original, Ray Milland is trapped by his own web of lies and when he realizes that he's screwed, the expression on his face is priceless. He's hauled away in disgrace to await trial by a jury of his peers. It's very satisfying, actually. The remake eschews this kind of "complexity" in favor of a gunfight at the end, during which Michael Douglas is killed off and not made to suffer due process or any further humiliation for trying to murder his wife. Justice, in the contemporary, parlance, has been served, but it's a hollow kind of vigilante justice. It's NOT satisfying. Or at least, not to me. It's far too tidy. For a real-life analogue, I offer you the case of Ken Lay and Enron. Not only did Lay's untimely death deprive the victims of Enron's collapse the redress of justice, it prompted Lay's conviction to be set aside.

The living end of this was the end of Troy, a retelling of the Trojan War. The movie paints Agamemnon, played by Brian Cox, as the film's rat-bastard villain. But I'll get to that in a moment. The ostensible source for Troy is The Illiad. If you ever read the poem in high school, you would likely have been annoyed at the changes made to the text, but for the most part, it gets things right. You get the wrath of Achilles ("Sing to me, o' Muse of the wrath of Achilles, the man-killer") and you get the ultimate tragic scene from the end of the poem where Hector's father, Priam, comes to Achilles tent to beg for the body of his mutilated son, Hector). If the filmmakers had had the genius of Homer, they would have ended it there, where Homer himself ended it. Then the film would have been a tragic epic worthy of milennia of stories about the Trojan War. But American audiences demand more. They demand "resolution" to even the most meaningless of plot threads. So we get the Trojan Horse. We get Achilles's death from an arrow in his heel. And we get Agamemnon's death...wait...Agamemnon didn't die at Troy. He sailed home with the prophetess, Cassandra, only to be murdered by his wife, Clytemnestra and her lover. Not in this version, though. Here he gets killed for the audience's sense of "justice," in which villains are slain at the end of the last reel. Villains can never be seen to prosper. Oh no.

Puh-leeze.

Are American audiences such uncomprehending sheep? Is the only satisfying end for a villain his death, whether from a gunshot, a fall from a high place, or a sword through his chest? How far has drama fallen? And what does this do to our cultural mores? American studio movies are largely junk anymore and it troubles me, not just because I love the artform, but also because I hate the underlying ethical assumptions behind them. But mostly, I hate the idea that audiences are in the grip of a media that has no more regard for their individual judgement than that held by the Communist Chinese. That disturbs me, actually.

Edit: Oddly enough, I'm not the only one to notice these things. Critic/Film Scholar David Bordwell notices some of the same things. So I'm not crazy after all...

No comments:

Post a Comment