"The fool, the meddling idiot! As though her ape's brain

could contain the secrets of the Krell!"

Made by a human being. AI is the death of culture.

Pages

Monday, December 03, 2007

Movies for the week of 11/26-12/2/07

On the other hand: To's Election 2 (2006, aka: Triad Election) is, if anything, even blacker than the style with which it is filmed. Picking up the threads from the first movie, we find Chairman Lok (Simon Yam) coming to the end of his term, and scheming to extend his rule contrary to triad custom. We also find Jimmy (Louis Koo) in the Michael Corleone role, a gangster who thought he was out, but who got dragged back in anyway. Having framed the romance of the Hong Kong crime film in the first two thirds of the first film only explode it in the end, To begins this film in a much darker mode. It's easy--poisonously easy--to see these films as a riff on The Godfather, but I think the true source is Kinji Fukasaku's Battles Without Honor and Humanity series. In the first of Fukasaku's films, the director mocks the yakuza sacrifice of fingers as penance for transgressions against their bosses by throwing one of those fingers into a chicken coop, where it is promptly devoured. To goes that one better in a scene of baroque nastiness involving a dog kennel, a cleaver, and a meat grinder. If the audience was making the mistake of sympathizing with Koo's Jimmy, this sequence obliterates it. Everyone here is a soulless lowlife. And that's where the movie becomes most interesting, because in addition to the triad machinations, there is also the specter of the government. Jimmy doesn't want to be a gangster, but the authorities on mainland China WANT him to take over the triad. To is cagey--he knows the game of pleasing the censors while saying what he wants. This is a masterclass in that kind of gamesmanship.

Milos Forman's Amadeus (1984) is witty (the title, in addition to being Mozart's middle name, is a terrific verbal bon mot). But it's not particularly good. Oh, the movie covers for the fact with lush production values and all the Mozart you could ever want, but the performances are stiff and the resolution is ridiculous. Still and all, I was surprised to learn that the god-awful laugh that Tom Hulce invented for Mozart was based on historical fact (a contemporary described the real Mozart's laugh as sounding like steel rubbing over glass). File this in the category of entertaining bad movies.

Peter Jackson's remake of King Kong (2005) is as shameless a love letter to a favorite movie as has ever been penned, but it's not an unreflected one. Especially in its extended edition, the movie echoes the original scene by scene (and occasionally frame for frame), but it manages the not inconsiderable feat of offering subtle, and occasionally scathing criticism of the original point by point. Consider, for example, the use to which Jackson puts Max Steiner's original score and the costumes worn by the natives in the original in a scene that lays bare the colonialist racism of the first film's natives. The film also difuses the weird (and racist) Freudian innuendo of the first film and places a character into the film that sympathizes with Kong as much as the audience does. But, of course, what's of real interest here is the dinosaur mayhem and the swarm of biplanes, and here, Jackson delivers in spades. Some viewers have called these scenes excessive, but when has Jackson ever delivered restraint? It's not in his nature.

Monday, November 26, 2007

Innocence and Experience

Anyone who doesn't know the intended direction of George Romero's zombie movies can be forgiven for looking at Andrew Currie's Fido (2006) and wondering where the hell that came from. Romero had intended to steer his series towards a new society where zombies are controlled by enclaves of humans, used as servants, and even used to wage wars. Fido is a logical extension of that, presenting a post-zombie world in which zombies are kept as pets. This is what you might get if you crossed Lassie (Timmy's in trouble! Go get help, Fido) with Land of the Dead and salted it with a generous helping of Douglas Sirk for good measure. Include a generous helping of good actors, including Carrie Anne Moss, Billy Connoly, Dylan Baker, and Tim Blake Nelson, and you have a recipe for a cult classic, right? Well, in theory, I suppose. It's all well and good to include a Sirkian subtext of frustrated sexuality in a stifling fifties sitcom world, but it's quite another to lace the entire movie with a not so subtle undercurrent of necrophilia. It makes for a creepy viewing experience. And not creepy in a good way. Plus, it's not as funny as the premise would suggest. It's not awful, but it's a misfire none the less.

Speaking of misfires, has it really been twenty years since Paul Verhoeven came to Hollywood? Jesus, what a waste. That waste is highlighted in his first film in six years (his last was the nigh-unwatchable Hollow Man), for which the director returned to his native Holland. Black Book (2006) shows why Verhoeven mattered in the first place, all the while giving license to the excesses that led him so far astray. The good stuff: Carice Van Houten is going to be a major star. Mark my words. She's the actress Verhoeven always wanted (in Sharon Stone or Renée Soutendijk) but never had before now. There's also a certain playfullness in the way the director and screenwriter Gerard Soeteman booby-trap the cliches of the WWII thriller, culminating in a bitterly ironic twist of the tail at the end. I mean, I can hear Verhoeven chuckling at the very notion that the Nazis could be heroic and that the resistance could be villainous (and overtly anti-Semetic). That's a perilous knife's edge that the film walks, especially given that the movie starts with the massacre of a boat full of Jews who have been betrayed to the SS. But, Verhoeven being Verhoeven, he can't resist a scene in which van Houten brushes her pubic hair with peroxide to dye it blonde. Nor can he resist the excessive defilement of his heroine when she's tormented as a Nazi collaborator. That all said, I'll give him props. This movie holds one's attention from scene to scene, and the film's running time unspools in a relative blink. I see that Verhoeven is heading back to Hollywood. Ah, well...

Friday, November 16, 2007

Early Hitchcock and Favorite Horror Movie Posters

Young and Innocent (1937) is an early variation on Hitchcock's "man wrongly accused on the run" movies, following on The 39 Steps a couple of years earlier. It's certainly energetic. Of the early British Hitchcock movies, this is the one that seems most like his Hollywood movies. Clearly, he had become a prestige director by this time, and the higher budget is on full display in two sequences: in the mine cave-in, which seems an arbitrary disaster like the plane crash in Foreign Correspondent; and the famed overhead shot of a ballroom that comes to rest four inches from the eyes of the killer (it's almost a reversed version of the final shot of the shower scene in Psycho, the one that dollies back from Janet Leigh's staring eye). But in a lot of ways, this movie isn't like Hitchcock's Hollywood films at all. Visually, it's loaded with quaint excressences the likes of which Hitchcock would strip out of his later movies, and some sequences show the director clinging to the visual shorthand of his silent movies.

Blackmail (1929) is a true sound/silent hybrid, and shows Hitchcock at his most inventive. There's a bold dynamism in his shot compositions and editing scheme in the silent portions of the film, and a kind of remarkable frankness in the sound material that would go underground during the director's long tenure laboring under the Production code. Hitchcock provides no title cards for the silent portions, but he doesn't need them (compare this to Rich and Strange, in which the sound portions are punctuated with title cards, perhaps tongue in cheek). With this film's climax, we find the first instance of the director staging mayhem in or near a monument as a means of contrasting order and chaos, a trope rumored to have been suggested to Hitchcock by Michael Powell. Unfortunately, the disc pixilated into a storm of digital noise at the end of the movie. The problem with the public domain is that you often get what you pay for, or, more accurately, when you pay peanuts, you get monkeys.

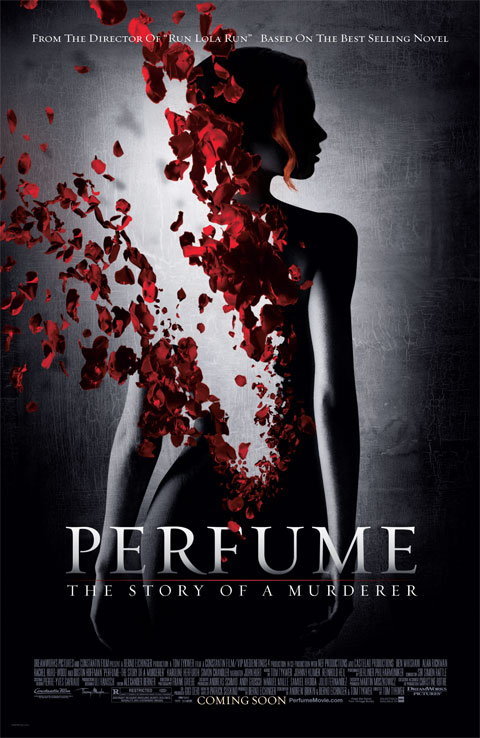

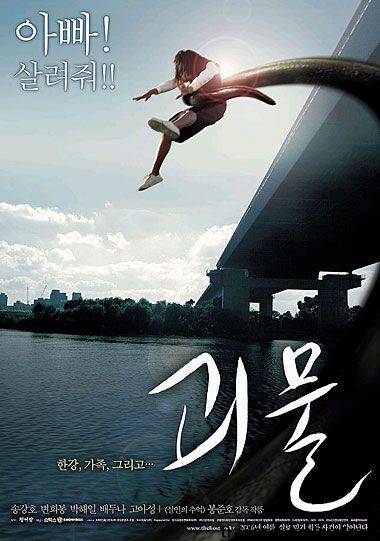

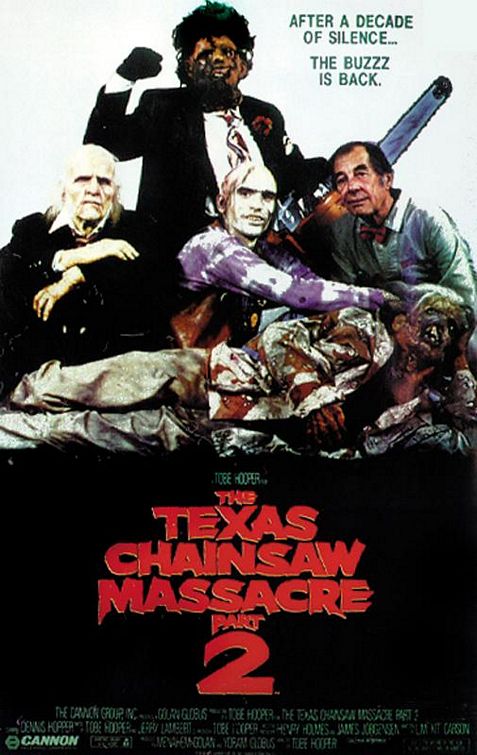

I was reading a lament that the art of the movie poster was lost. While I can certainly understand this sentiment, I think there are still movie posters being made today that stand with the best posters of yesteryear. Two of my favorites are from horror movies made last year.

I love, love, love this poster for Perfume: The Story of a Murderer:

I love, love, love this poster for The Host:

But this may be my favorite horror movie poster. It's for The Texas Chain-Saw Massacre 2:

Monday, August 06, 2007

One of the reasons I've always liked Bergman is because, of the major world directors, he's the one who seems the most like he's making horror movies. His ongoing conversation about the silence of god is fraught with horror, as is his assessment of the existential state of human beings in the face of that silence. It's commonly held that The Hour of the Wolf is the closest to a "pure" horror movie that the director ever made, but reaccquainting myself with Cries and Whispers makes me question that notion. Bergman's movies generally exist outside of genre, but many of his films have generic markers. If I were to "type" Cries and Whispers, I would call it a haunted house movie. Like the best such movies, it's a narrative that confines haunted people in a metaphorical microcosm. The dominant red of the house--Bergman calls it the color of the soul--suggests to me the interior of a body, like the house itself is an organism. The persistent use of disolves, in which the faces of the characters fade to red, subsumes the characters into the environment. And a fine cast of monsters we have in this film. Liv Ullmann's Maria cuckolds her husband and fails to lift a finger when he stabs himself over it. Ingrid Tullin's Karin is an island, incapable of human contact or feeling. Neither can bear the thought of death, as incarnated by their sister, Agnes (Harriet Andersson), who they rebuke on her deathbed. Only their servant, Anna, seems fully a human being, and only she seems to have any faith in a god or in humanity. The others are bounded by Bergman's ever-present silence...or rather, the whispered voices from that silence--ghostly, or demonic, or psychological--that fill the interstices of the movie.

In comparison, Wild Strawberries seems positively antic. At one point, Bergman stages the conflict between atheisim and belief in God as a fistfight. The horror imagery is still there in the form of two dream sequences, but, like Scrooge on Christmas, our hero, old Professor Borg, finds both catharsis and human contact from his dark night of the soul. Still and all, it's interesting that he describes one of his dreams as "vivid and humiliating."

In any event, I need to visit (and re-visit) Bergman more often than I do.

Fred Zinnemann's Act of Violence (1948) was first out of the box for me upon receiving the latest of Warner's film noir boxes. I've written a long review of this for my web-site, which can be found here: http://members.tranquility.net/~benedict/actofviolence.html

I also caught up with Caged (1950, directed by John Cromwell), a film that has been eluding me for some time. When I saw that this was being released as part of the "Camp Classics" sets, I lowered my expectations. I mean, if Warner considers this as being on the same level as Trog then it must be REALLY bad, right? Well, no. It doesn't belong in that set. It's a pretty damned good film noir, a refreshingly serious women in prison movie, and a showcase for Eleanor Parker. The arc of the story, in which Parker's virtuous, wrongly convicted Marie Allen is hardened into a femme fatale by the screws and inmates of her prison, is a distaff version of Nightmare Alley, which is no small compliment. I love Agnes Moorehead in this movie, playing against type. Given the subtle lesbian coding in the film, it amuses me that Moorehead should be the socially crusading warden. Funny.

Wednesday, May 09, 2007

Movies for the week ending May 6, 2007

For anyone who complains about how "bad" Spidey 3 is, I would direct them to one of the other films I saw last week, My Super Ex-Girlfriend (2007, d. Ivan Reitman), about which I will have nothing further to say, except to note that nothing makes a good movie look better than an awful imitation.

I also finally got out to see The Host (2006, d. Bong Joon-ho), which has been described as Little Miss Sunshine meets Godzilla. While I won't dispute that characterization, it's better than that. A number of other reviews have noted that this is a movie that refutes the monster-movie playbook point by point, which is closer to the truth. For all that, I suspect that the true motivation behind the movie was a love of monsters and an impatience with how they are usually depicted. I'm sure you know the drill. A few teases early in the movie. A tail here, a footprint there, tease, tease, tease for a couple of reels before the big reveal at the beginning of the third act. Monster movies from The Beast from 20000 Fathoms to Dragonslayer use this same story structure. The Host says screw all that. In the first reel, you get more monster mayhem than many monster movies include in their entire running time, mayhem filmed in broad daylight, with the best "innocent crowd fleeing a monster" scene I've ever seen. It's a cool damned monster, too. It's not as good a film as director Bong Joon-ho's previous Memories of Murder, but it's close, which is high praise.

I also found The Professionals (1966, d. Richard Brooks) in the dump bin at Wal-mart last week for four bucks. This is one of my favorite westerns, with great performances by Lee Marvin, Burt Lancaster, and Robert Ryan and a very yummy Claudia Cardinale. It's a film that blows sh t up real good, too. A total "guy" movie, one that reeks of testosterone. I've loved this flick since I saw it with my dad as a teen. I had very odd thoughts while watching it this week, though, largely inspired by the media furor over the VT massacre. This is a movie in which there are dozens of people violently killed on screen, whether from gunshots or explosions, and I got to thinking about how out-of-kilter our value systems are when it comes to depictions of violence, especially in comparison to horror movies. In The Professionals, we root for the killers and exhult in their actions. We WANT them to kill the bad guys. But let's compare that to, say, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, in which there are only four people killed,in which the killers are impenetrable cyphers. The filmmakers consciously skew the movie so that not only is the audience NOT invited to root for the killers, their actions are designed specifically to inspire horror. And yet, a film like The Professionals is more socially acceptable than a film like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. TCM is occasionally thought of as a "sick" or "depraved" film, while no such criticism attaches to The Professionals. What does that say about our society? I don't know. I'm just speculating out loud.

Monday, February 19, 2007

Movies for the Week Ending 2/18/07

Leo McCarey was convinced that the Cary Grant persona was an impersonation of himself, learned by Grant on the set of The Awful Truth (1937). I doubt very much that this is wholly true, but I suspect there might be a kernel of truth to it. Grant, the chameleon, picked up bits and pieces of a lot of the people he worked with. But to my eye, the Grant persona was already in place as early as Sylvia Scarlet, two years prior to The Awful Truth. That said, it’s possible that The Awful Truth shows the Grant persona perfected. The movie itself is great fun, and Grant’s deft self-deprecation is one of the film’s main attractions. Watching him spar with co-star with Irene Dunne as they both try to wreck the other’s happy divorce is a delight. I used to love the Dunne/Grant pairings, but time hasn’t been kind to them. Dunne seems woefully out of her league, a creation of the 1930s, while Grant seems timeless. This probably works the best of them, though, and the look she gives Grant from her bed at the end of the movie is a look that I can imagine on the faces of a lot of women were Cary Grant to walk into their bedrooms.

Most of the reviews of Johnnie To’s Breaking News (2004) focus on the opening shot. It’s a great shot, so I’m not going to quibble with this, but the consensus seems to be that, outside of that shot, the rest of the movie is rote. I’m not so sure about that. There are two things in the movie that set it apart from standard Hong Kong actioners: The first is the sly, meta-cinematic reworking of Johnny Mak’s Long Arm of the Law (1984)--in both films, a gang of criminals is trapped by the police in one of Kowloon’s mammoth apartment blocks. It’s commonly thought that the satiric point of the movie is trained at the media--and it is--but it’s also trained at the history of the Hong Kong action film itself. Most viewers won’t catch this, or even care about it, but I liked it. The other thing that sets it apart is the measure of everyday life that our gang of criminals brings to their ordeal. They take a family hostage, discover that the father (To regular Lam Suet) cannot cook, and end up making a feast for the family. Both of our criminal masterminds dream of opening restaurants. It’s a totally unlooked-for flourish in a film that could be a routine programmer. We also get still more variations of the director’s obsession with cell phones, which marks this distinctively as a To film. To may be my favorite director on the Pacific rim right now.

In the interests of full disclosure, here’s how I stand with Robert Bresson: I was indifferent at best towards both The Trial of Joan of Arc and Diary of a Country Priest. I hated Au Hasard Balthazar, which may be the most disgustingly misanthropic movie I’ve ever seen. I was quite content to let sleeping dogs lie. I have plenty of other interests without forcing my way to an appreciation. In steps my significant other, who collects Arthuriana, with Bresson’s Lancelot of the Lake (1974). Now, I don’t know what I was expecting. Much as I disliked Balthazar, I’ll certainly admit that it was impeccably filmed, so I wasn’t expecting Lancelot to be as unwatchably awful as it turned out to be. For a brief moment at the beginning of the film, I wanted to pop it out of the DVD player to make sure that we were watching the right film. The opening sequence, consisting of various slaughter and mutilation of knights, seems like a first sketch for a Monty Python skit, or a poor-man’s imitation of the bloodier chambara set pieces from Japan, only with blood pumps set to “ooze” rather than “geyser.” The feeling that this was a half-baked sketch was reinforced by the constant, annoying clatter of armor. The film’s other signature sound effect is the whinny of an off-screen horse. The film repeats this sound effect--the same, unvarying sound effect--at random throughout the movie--and, again, I began to think of Monty Python (the resemblance between this and Monty Python and the Holy Grail is too close to be an accident). The film has no interest in people, except, perhaps, to delineate how awful human beings are. Bresson communicates this through his zombie actors and by a desire to look at anything but a human face except when he can’t get around it. There are a LOT of shots of the feet of knights and the feet of horses in this movie, so many that it becomes ridiculous, even at an 80 minute running time. In his desire to deny the audience the pleasure of romance or spectacle--and I’m sure that this is the intent--Bresson elides anything that might be considered a set-piece, resulting an a completely disjointed narrative as the film comes to its climax. We see aftermaths, mostly, but we don’t see context. After we finished watching this movie, my GF said “Well, that’s two hours I’ll never get back.” I didn’t have the heart to tell her that it was only an hour and twenty minutes. Such is the relativistic, time-dilating effect of really terrible movies.

I think I’m done with Bresson.

99.9 (1997) is another film by Spaniard Augusti Villaronga, whose other films ambushed me late last year. Villaronga knows how to get under the skin. He knows how to give the knife a twist or two beyond what the audience thinks it can bear. He’s on speaking terms with horror in a way few directors can manage for long. This film is no different. It follows the host of a radio show as she tries to unravel the death of a friend who died under mysterious circumstances while conducting paranormal research in a small village in Andalusia. The plot has an Asian feel to it, on the surface. Parts of the film, detailing our heroine’s friend and his work, mine the videodromic dread of The Ring and its progeny. But unlike those films, the film ultimately has a little-c catholic view of horror and evil. Evil in Villaronga’s world is part of the air. It’s everywhere. It’s wherever you find it. That all said, this isn’t nearly as alarming a film as In a Glass Cage. Its focus is far too diffuse. Villaronga follows a number of narrative dead ends as a result. The film doesn’t add up, exactly, but when it is clicking, it remains as bruisingly hurtful to the audience as the director’s other films, only with less of a point. He’s traded scalpels for an aluminum baseball bat, if you will, but both will screw you up bad in the right (or wrong) hands.